The Great Cobalt Silver Discovery

The fabled Klondike gold rush had gone into decline and those who had won and lost fortunes had begun the trek from Dawson City to Alaska or to whatever other areas the Goddess of Fortune called them, when new and, in the long run, much more significant events took place in the hinterland of Northern Ontario. Silver at Cobalt! Cobalt came into being almost overnight, totally unplanned and without advance notice. At the turn of the century there were few geological maps and little suspicion of the existence of the widespread mineral deposits that have since made the Canadian Shield of Precambrian rock one of the world’s greatest treasure troves.

A few hardy farmers were breaking ground in the rich clay belt north, east and west of Lake Timiskaming. Their centres of population were the villages of New Liskeard and Haileybury. The Hudson’s Bay Company had a fur trading post not far away but its agents had failed to detect the other, greater, form of wealth. A certain amount of timber was being taken from the heavy forest and floated down Lake Timiskaming to the Ottawa River on its way south, but the lumbermen kept their eyes on the tree tops while their boots scuffed over the veins of silver ore.

In G. C. Farr, a former factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, the Little Clay Belt had a strong protagonist. After his retirement from the Company’s service he had secured a land grant which included the present site of Haileybury. Largely as the result of his campaign to convince southerners of the importance Or Northern Ontario’s agricultural potential, the provincial government sent in a team of experts to assess the possibilities.

So favourable was their report that the government decided to finance the construction of a railroad from North Bay to open up the country for full development of its agricultural possibilities and its forest resources.The line inched northward, skirting lakes, spanning rivers and blasting its right-of-way through solid rock.

At mileage point 103 it passed directly over rich silver veins, and there came the discovery that was to make Cobalt a household word throughout Canada and the whole mining world.

Credit for the discovery belongs to J. H. McKinley and Ernest Darragh who were engaged as contractors to supply ties for the railway. On August 7, 1903, while cruising the Booth Limits for timber, their eyes were caught by the gleam of metallic flakes in the rock at the southeast end of Loog Lake, later re-named Cobalt Lake. They found other flakes in the gravel on the beach, found that they were soft enough to mark with their teeth and so pliable that they could be bent. They sent a number of the rock samples to Montreal for assay, and the word came back that what they had submitted was native silver, assaying 4,000 ounces to the ton.

It was a glittering prospect, and the two applied for and received a mining lease from the government. The following spring they did further prospecting and erected a small plant. The first claim was dubbed “J.B.l” and the first chapter of Cobalt’s rise to fame and fortune was begun. On this claim grew the McKinley-Darragh mine.

A few weeks later, as the story goes, Fred LaRose, a blacksmith at work at his forge, was so annoyed by an inquisitive fox that he threw his heavy hammer at the animal, missed it but knocked off a piece of rock to expose a glittering vein of silver. This became the LaRose Mine, and probably never in history has so haphazard a method of rock sampling yielded such rich dividends.

LaRose showed some samples of the rock to Arthur Ferland, proprietor of the Matabanick Hotel in Haileybury, remarking that it seemed to contain “some kind of damn metal”. Ferland in turn showed the rock to T. W. Gibson the director of the Bureau of Mines. Gibson identified the mineral as niccolite, an ore rich in nickel, and forwarded it to Willet Green Miller, Ontario’s first provincial geologist, with a note which said in part, “If the deposit is of any considerable size it will be a valuable one on account of the high percentage of nickel which this mineral contains. I think it will be almost worth your while to pay a visit to the locality before navigation closes.” It was only after the samples had been examined by A. G. Burrows, the provincial assayer, that the mineral content was recognized as predominantly silver.

Miller lost no time in following up his chief’s suggestion that he visit the scene. It was late in October when he arrived and he made good use of the time that was left for examination before the winter snow would cover the ground.He found that openings had been made on four veins, and from three of them large lumps of a heavy metal had been taken. The prospectors did not know what this metal was but Miller was able to tell them that it was silver, and very rich silver at that. Nickel was there too, but only as a minor constituent.

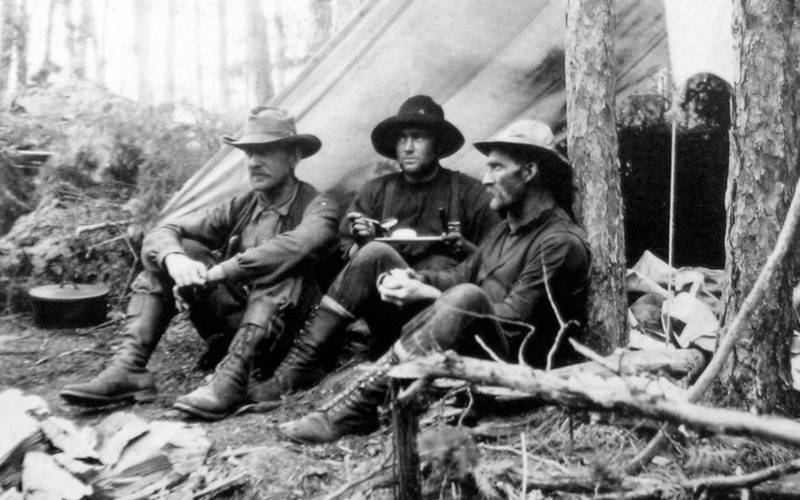

Miller was a government geologist – by definition an ultra – conservative – and the report he wrote of what he saw on that visit and another in the following year in which he led a full – scale geological survey party, was probably one of the most optimistic documents of its kind ever prepared. His assistants in the field were two young men, Anson Cartwright and Cyril W. Knight, whose names were destined in later years to become known wherever mining was discussed in Canada. In his report he spoke of “pieces of native silver as big as stove lids or cannon balls lying on the ground, as well as cobalt bloom and niccolite.”

The report was, perhaps, his major service to the infant mining camp, but while he was there he performed another in giving it a name. On the shore of Long Lake he set up a crudely-lettered board which read “Cobalt Station T. & N.O. Railway”.

In Cobalt’s famous square stands a memorial monument of the native rock to which is affixed a plaque bearing this testimony to the debt which Cobalt and the people of Canada owe to the man: “To Cobalt he gave its name and its place among the great mining camps of the world. He read the secret of the rocks and opened the portal for the outpouring of their wonderful riches. His monument is New Ontario.”

Just about the time that Miller first arrived in the new mining camp in October, 1903, another major discovery was made by Tom Hebert who staked out the property that was to become the Nipissing Mine. More than half a million dollars’ worth of silver was subsequently extracted from a single vein.

The mining world, which had displayed such monumental indifference following the first discovery, was jolted out of its complacency when Trethewey’s first shipment reached the south. T. W. Gibson, writing later in his history, Mining of Ontario said, “These shipments consisted of slabs of native metal stripped off the walls of the vein like boards from a barn. It is difficult for a later generation to realize how greatly the public mind was intrigued by the evidence that a virgin field of unusual richness had been opened for exploitation.”

If Ontario was caught unprepared for the advent of Cobalt, certainly Cobalt was equally unprepared for the inrush of honest prospectors, claim jumpers, fortune hunters and eager novices that followed. Almost overnight the whole of Coleman township was studded with the corner posts of mining claims. Never in Ontario had such intensive prospecting activity been seen, and every crack and cranny in the rock, however small, was examined with the most minute care, for it could contain a king’s ransom.

The town of Cobalt itself sprang into existence on the bare rock in the middle of the mining area. It grew entirely without planning, and wherever a flat outcropping big enough to support a building could be found, there was the site of a miner’s home. Cobalt, with its erratically curving streets and its generally haphazard construction still bears the marks of its pioneer heyday. Aesthetically Cobalt may not be the community planner’s ideal – but never should that be whispered to its loyal residents who claim with complete justification that there has never been and never will be another Cobalt.

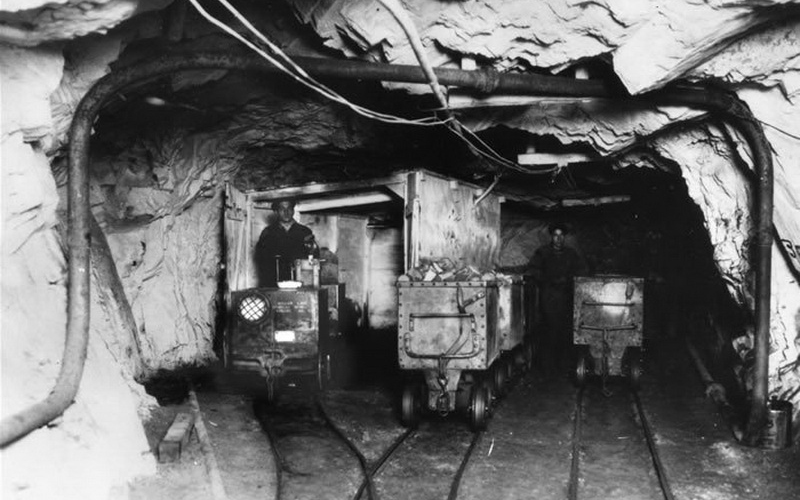

In a sense Cobalt has always been a “poor man’s mining camp”. Because most of the rich mineral-bearing veins lie close to the surface, very deep mines and costly operations have never been necessary. Generally the individual mines were not large or elaborate operations such as may be found in other areas of Northern Ontario, but the ore was sufficiently rich and plentiful that such large plants were not required.

In the first 60 years of its active life, the mines of the Cobalt camp shipped a total of nearly 1,185,000 tons of rich silver ore and concentrates. The total production in that time exceeded 420,500,000 ounces of silver. At today’s price of silver, the amount is staggering. To ship the ores and bullions extracted from the mines of the camp during those years would require a train of freight cars nearly one hundred miles long – stretching down the track all the way from Cobalt to North Bay, 140 km.

It was inevitable that the cream of the silver harvest should be skimmed off in the prodigal days of fast and easy money. Only the richest ores were recovered and fortunes were left quite undeveloped. Thus it came as a double disaster that at the same time the market for silver dried up, so did the supply of readily available and inexpensive ore. Cobalt was – in the opinion of most observers a dying town. The solution was at hand and Cobalt found its salvation in the mineral for which the town was named – the mineral which, mixed with the silver ore had been only a nuisance, making the smelting and refining operations much more difficult.

Science, the threat of war, and improving technology all had a part in Cobalt’s revival. The mineral cobalt, long used in the form of an oxide in the ceramic industries, now found a host of other uses. At one end of the scale it was used in the Cobalt 60 Therapy Unit (the Cobalt Bomb) to fight the ravages of cancer. It s use as a heat-resistant alloy also made possible the development of jet engines for aircraft . Because of its extreme hardness when alloyed with chromium to form “stellite” it is widely used in the manufacture of cutting tools. It has its place in the manufacture of nylon and in agriculture as an additive to cattle feed. Cobalt indeed is one of the world’s most versatile elements.

A key drawing card for visitors to the area, the Cobalt Mining Museum offers a display of relics from the early days which is warranted to produce an attack of acute nostalgia in any old timer. This museum has grown steadily and extended its scope so that it is now considered one of the best in situations of its kind in Canada.